Making Sense

Through his exhibition Making Sense, Ai Weiwei is ‘trying to tell us something about the state of the world’ [exhibition leaflet, the Design Museum, 2023]. Ai can’t be accused of lacking ambition. This broad ranging show does not disappoint. At every turn we are invited to question, to ponder and to wonder.

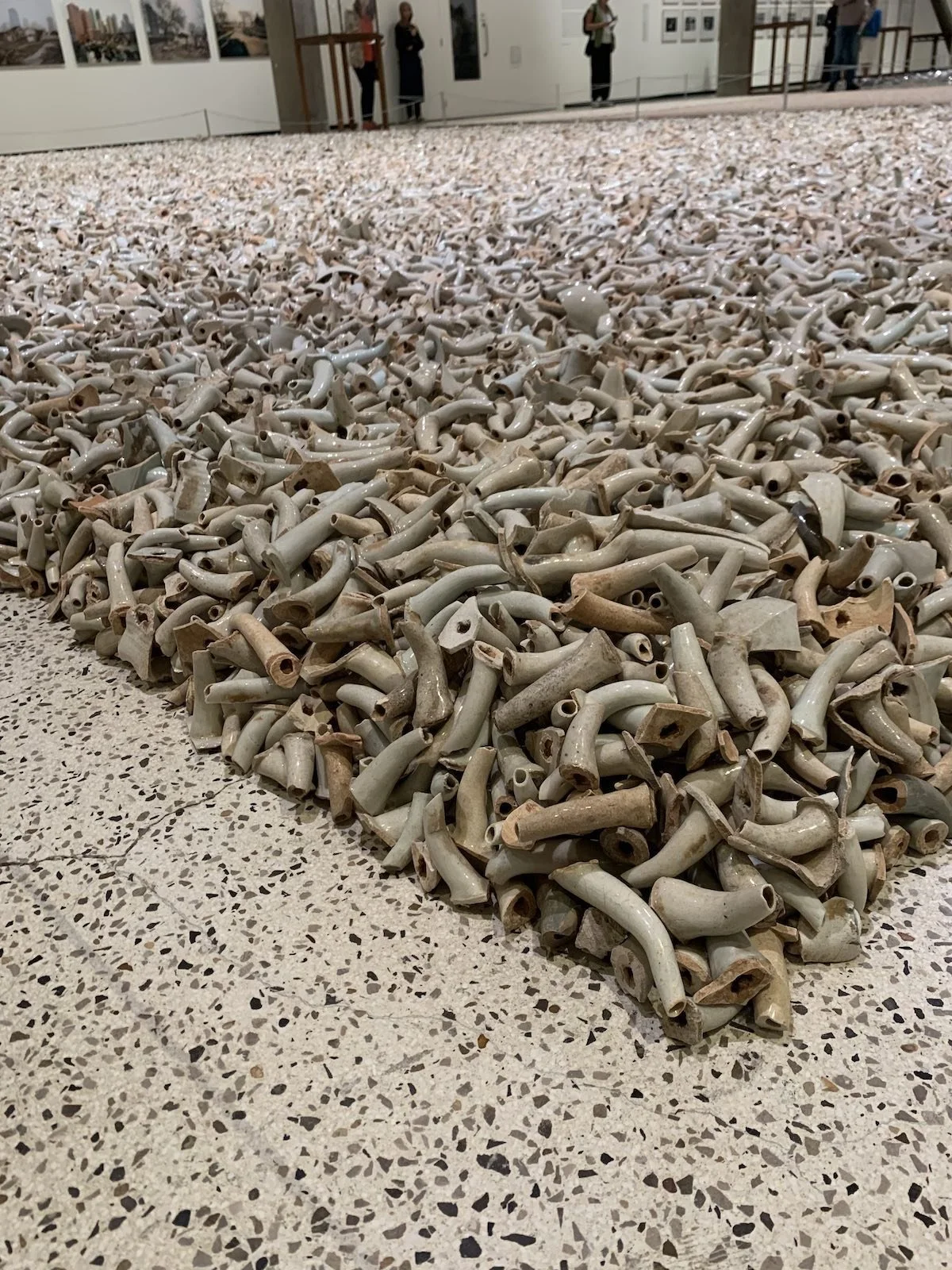

There are no dividing walls, the space is open, the different works jostle for our attention and yet the initial impression is one of calm and order. The floor space is divided into a grid of rectangular fields of varying materials. The most garish of these, Untitled (Lego Incident, 2014), is made up of Lego pieces to the artist by the public to enable Ai to continue making portraits of political prisoners when the parent company briefly refused to send him bricks. The next field, (Left Right Studio Material, 2018), consists of a bed of broken blue glazed porcelain pieces, a reminder of the destruction of Ai Weiwei’s studios by the Chinese authorities in 2018. In the next field, Untitled (Porcelain Balls), 2022), more than 200,000 porcelain cannonballs illustrate Ai Weiwei’s interest in collecting objects, often ancient, of no great intrinsic value. These illustrate the scale of mass production by hand in China over one thousand years ago, in the pursuit of conflict. In the next field, the porcelain spouts, broken off substandard ewers and teapots, Untitled (Re-firing Spouts from the Song Dynasty, 2015), are disturbing. They appear poised to writhe and rebel in the face of repression.

Ai Weiwei, Left Right Studio Material, 2018

Ai Weiwei, Spouts, 2015

In contrast, the last field (Still Life, 1993-2000) I found calming and beautiful. Laid out methodically in an organised, single layer, the similarities and differences attest to the hands that made them. Absent here is the quest for identical perfection, replaced in these stone artefacts by the ghostly presence of the humans who made them, before society became a monolith. In this exhibition, people are only seen in the films and photographs and yet they are everywhere, makers, artists, citizens, displaced in the name of progress, repressed by authoritarian regimes, killed by shoddy workmanship. Below the surface composure, visitors cannot ignore tensions: tensions between the old and the new, the individual and the state, the old ways and modern values. In juxtaposing past and present, superimposing modern branding on ancient artefacts and offering collections of ancient but worthless objects, Ai Weiwei scrambles perceived notions of value, asks us to consider the worth of skills, traditions and history.

Ai Weiwei, Still Life, 1993-2000, Stone

I left reminded of many horrors and disasters and yet, ultimately, optimistic. Ai Weiwei’s social and political commentary shows us that resilience overcomes, that the human spirit can prevail.