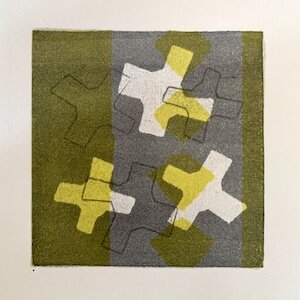

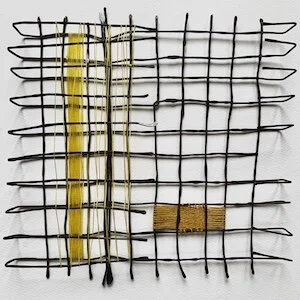

The materials have not only changed in scale, but also in nature. There has been a growing awareness of the questions which can be asked by the juxtaposition of different elements: the yielding nature of the thread against the hardness of the marble, the disarray of the tangled skein set against the tension of the taut line, the weight of metal anchoring a suspended paper structure. Does the meaning of the work, what Marcel Duchamp refers to as ‘the work of the work’, sit in the liminal space between the physical and the ephemeral?

The texture of the materials invites the viewer to experience the work as a whole body experience. Merleau-Ponty asserts that we decipher our environment, the world we live in, our position in it, by using all our bodily senses. In contrast to the philosophical view that consciousness is the locus of this knowledge, Merleau-Ponty posits that we encounter the world through our bodies. Texture engages with memory. Though we may not be allowed to touch something, the act of looking alone can trigger our sense of touch by engaging our stored textural recollection and thus allowing the viewer to become more fully involved with the work.

The tactility of the materials is part of the message. The texture of the materials from the smoothness of bone or the roughness of rope to the coldness of metal are triggers for our senses beyond mere sight. Through these sensations it is hoped to trigger a greater awareness of how we connect to the world around us and how we might lead more stable and grounded lives.

In his theory of hyper-reality, Jean Baudrillard asserts that it is no longer possible, in post modern culture, to separate reality from representation. The real, the artificial and the copy are now indistinguishable. Only simulacrum remains. Not only do we live our lives through the filter of social media, but the function of places has become blurred. The work space can be an office, home, train, bus or even a coffee shop. How often do we photograph landmarks rather than look at them? The experience of being in a place has become subservient to the making of, often digital, memories. Earphones separate us from our environment and from the people around us. While we naturally engage with both existent communities as well as digital communities, the purpose behind these works is to celebrate the connections we have with the place and spaces in which we live.

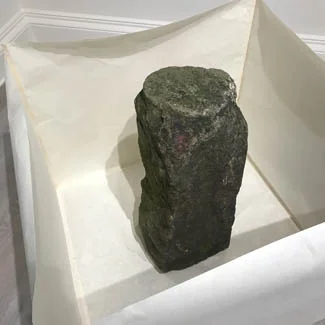

As a reaction to the new reality, my work uses physical objects to explore what it is to be human and our connection with the world in which we find ourselves. The use of materials such as bailing twine provides a clear link to agrarian communities and the land on which much of our livelihood still depends. The juxtaposition of antithetical materials such as the plastic twine and animal bones seek to emphasise the role of the human in the husbandry of the land and our place in the world among animal and plants.

Most of the elements in the work are made of mundane matter and carry none of the value associated with precious materials. The reference is not to monetary value but rather to the value of manual labour and of having the skills required to forge an embodied life.

The use of found and gathered objects in the work offer a visible link to history and of creating a concrete connection to craftsmen in a past we cannot know. Well made tools were treasured and the marks of time they carry should be read as a badge of honour, a testament to the skills of previous owners, bringing to mind William Morris’s vision to create meaningful everyday possessions. The survival of these tools and artefacts attest to the authority vested in the objects. These are representations of skills we may be in danger of losing.

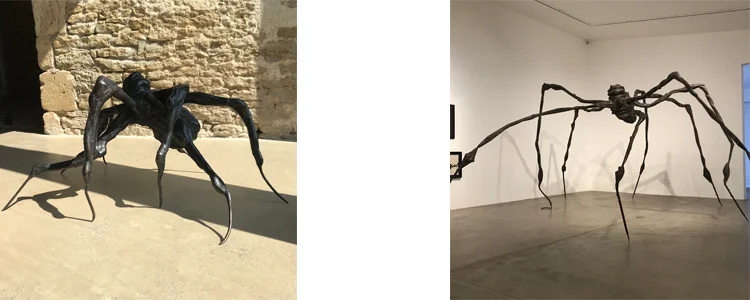

The knot securing the animal skull is reminiscent of a noose. The brutal allusion is intended to encourage the viewer to confront our mortality and to act as a reminder that all life is transient and is something to be appreciated and treasured.

First, when I work, it’s only the abstract qualities I’m working with, which is the material, the form it’s going to take, the size, the scale, the positioning, where it comes from – the ceiling or the floor. However I don’t value the totality of the image on these abstract or aesthetic points. For me it’s the total image that has to do with me and life. (Hesse, quoted in George 2014:91)

Curation and exploration of site

The intention is to develop the practice with a focus on curation and the way forward is likely to include making and showing work in places outside of or away from traditional gallery spaces. The standard white box offers a passive environment in order to focus attention on the art works themselves. The conversation between object, site and meaning is a multi-layered one. The location adjacent to a sculpture inevitably brings with it its own memories and associations. The viewer too will read the site according to his or her history. An outdoor site is less controlled than an indoor one and is likely at the very least to be subject to variations in the weather.

To disseminate the work in non-standard situations is to invite the possibilities for more spontaneous and for less formal and more casual engagements with viewers in unexpected circumstances. The dismantling of Land Line on the Surrey Heathland was paradoxically more interactive that setting up. This may of course have been pure chance or, with several weeks between setting up and taking down, a function of the seasons and weather conditions.

The Apopoclectic show by MA students in the James Hockey gallery allowed works to breathe and inhabit their own space. The generous gallery space encouraged the display of work in a manner which encouraged thinking about how the curation affected the message. As we experience works relative to our bodies, the placement of elements high on the wall or low on the ground will require some effort of the part of the viewer. Our field of vision will require us to stretch our gaze upwards and to lower our gaze, perhaps bending over slightly to look at elements placed on the ground. The absence of a plinth removes a formal element and allows vernacular presentation, more suited to the message.

![Roly’s Sweater, original sweater knit and mended by Elizabeth Cobb with additional repair in blue wool, 67 x 81cm, 2007 [image from http://celiapym.com/]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/583000cf2e69cfe8eaba9fdc/1550748357713-5A5WNIOP9ZB4Q9LQ7FTZ/Roly%27s+Sweater.jpg)